Mary Szybist on Visual Poetry

The first visual poem I loved is not really a visual poem—or rather, it was not created to be one.

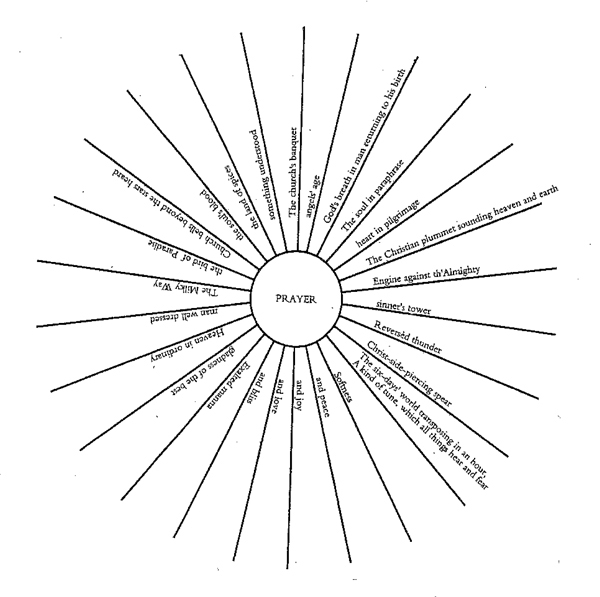

I had loved George Herbert’s “Prayer”—intensely, beyond reason—for many years, and from the first moment I turned the page in Helen Vendler’s textbook Poems, Poets, Poetry to see her sunburst rearrangement of the sonnet, I found it deeply satisfying and beautiful.

I stress “from the first moment”; the form made the syntactical structure thrillingly visible, instantly apprehensible. By placing the word “prayer” in the center with all modifying phrases radiating out like spokes on a wheel, the sentence’s symmetry becomes unmistakably clear: every phrase in the poem is a metaphor for prayer. This visual rendering also enacts the poem’s grammatical incompleteness. By beginning “Prayer the Churches banquet, Angels age. . . ,” Herbert drops the expected “is.” Without a main verb, the sonnet is an incomplete sentence, a subject followed by a list of metaphors. The visual rearrangement enacts the suspended, verb-less world of the poem. Everything has equal weight, everything is attached to prayer as if by an equals sign.

It was Simone Weil who first inspired me to memorize this poem, knowing that she had memorized and recited it often to herself while standing just outside of the church she was drawn to yet refused, watching the communion she longed for but of which she would not partake. I understood that. Vendler describes Herbert’s poem as one of “radical amplification”; it makes the concept of prayer larger, stranger, and more inclusive. Her rearrangement makes the poem seem even more inclusive, makes prayer seem like something open to me, something I could enter. In this version, one need not read in any particular order or even move through the whole poem: land on any “spoke” and it takes you directly to “prayer.”

If the sonnet gains a more radical sense of openness through Vendler’s re-arrangement, it loses something too. As Vendler insists, “Because poetry is a temporal art, it has to unfold sequentially, one piece after another. First I say x, then y, then z.” As she notes, the poem may have a radial order, but it also has a temporal one. In Herbert’s original sonnet, we do not “choose our own adventure” of prayer as we might in the sunburst version; we move through a human mind working out a concept and relationship to prayer as it reaches its understated end:

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well dressed,

The Milky Way, the bird of Paradise,

Church bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

Order matters. Even the “Milky Way” does not suffice, and the speaker must go beyond it, replace it with bird, bell, blood and “land of spices” before rejecting metaphor altogether to arrive at the transcendence that most matters: “something understood.” It is a trajectory we entirely miss if we happen to read the sunburst arrangement in a way that ends with “the church’s banquet.”

I want it both ways: I still recite the poem to myself with all its temporal drama, but as I do so, I picture the radial arrangement. Vendler’s point, as I take it, is that the original poem does contain both: her sunburst arrangement simply helps us understand the syntax that is already there, helps us understand the radial order along with the temporal one.

Still, this doesn’t fully account for why I so often find myself leaving Vendler’s book open to the sunburst page so my eye can land on it through the day. I want to see and touch it. It is an object I like to have around. It may primarily be an image of syntactical order, but I find it nevertheless an image that invites contemplation—largely due, I think, to its openness.

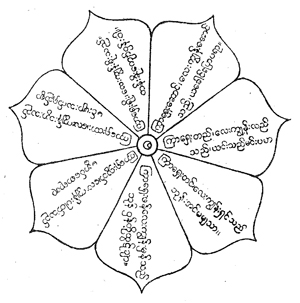

To turn to images shaped with words for meditative or spiritual practices is not a new idea. Aramaic cultures inscribed bowls with circular incantations believing that a demon would read “round the spiral until he reached the centre, and then, unable to read backwards, was caught forever” (Bowler, 7). In Burmese seven wheel jewel writing, the center word belongs to every line.

The lotus flower with its seven petals is often symbolic of the deity. In Shahin Ghiray’s Turkish ghazal or circle ode, the center word acts as both the first and last word of each line.

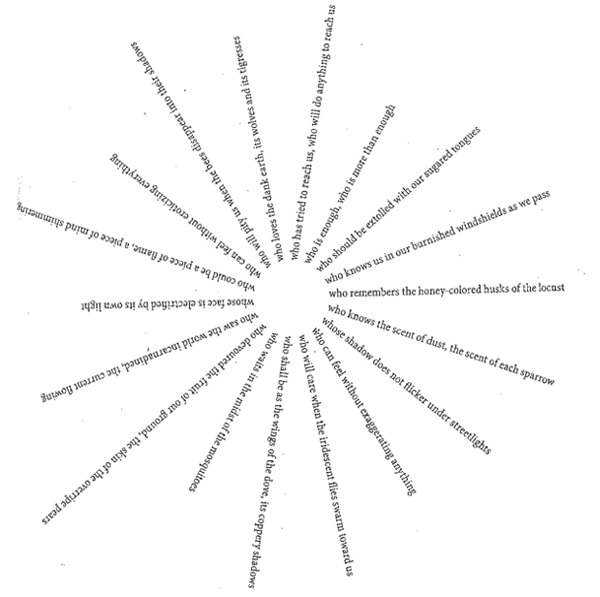

J. W. Redhouse translates the beginning of this long love poem as, “Let but my beloved come and take up her abode in the mansion of her love. . . If thou art wise, erect an inn on the road to self-negation, so that the pilgrims of holy love can make there their halting place” (Bowler, 127). I like the idea of a poem as a “halting” place on a larger spiritual journey. It was in this spirit—wanting my own meditative object—that I wrote my poem “How (Not) to Talk of God.”

I wanted to avoid a prescription for temporal order and invite the reader to drop in and stop at different places. God is in the title, but I did not place the word “God” in the center. I wanted to leave that open, blank, a subject that might be experienced as presence or absence. The modifying phrases ring to my ear as both as descriptions and questions. For example, “who had tried to reach us, who will do anything to reach us” both describes a god who cares for us and questions who is left to make such attempts in the absence of such a figure. I wanted to experience faith and doubt as entwined, simultaneous. I want each line to read as a declaration and as an open question. Just as I did not want the poem to read in a pre-determined temporal order, I did not want its shape to resemble a singular pictorial image such as a wheel or sunburst.

In other words, I do not think of the shape of the poem as a pictorial shape. I see it as the shape of the sentence’s syntax. If sentence diagrams were so clear, intuitive, and shapely, perhaps more of us would find syntax beautiful. (As a point of contrast in my book, I include a poem in the form of a sentence diagram—a very different way of imagining the shape of thinking.) It also strikes me that giving up temporal arrangement for a purely radial one opens the poems to multiple readings but also renders it strangely static, moves it closer to the realm of object rather than speech.

For this reason, I sometimes wonder if the poem works better as an object in the world than on the page. The poem was made into such an object, painted as a mural on the ceiling of the portico of the Pennsylvania College of Art and Design as part of a public arts project in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The Artist Team Room 222 designed and painted the mural.

Looking up at the poem—reading it by moving my feet, my body beneath it, weaving in and out of its lines felt far better to me than reading its lines by looking down at the page. Does this make it less literary—less of poem?

I don’t know. For a long time visual or concrete poems held little interest for me. They seemed overwhelmed by their visual gimmicks, as if they were only playing. I have thought a lot about Vendler’s claim that “poetry is a temporal art” because I have always loved poetry as sound in my ear and in my mouth. I continue to more fully appreciate, however, the diverse ways in which visual effects can collaborate with rather than simply overthrow the temporal, even when these collaborations take the form of disruptions. I believe that it is often in these disruptions to the temporal—which visual elements can achieve with direct and dramatic force—that contemplation is most fully allowed and invited.

—

Works Cited

Poems.Poets.Poetry, Helen Vendler, Third Edition (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2010)

The Word as Image, Berjouhi Bowler (London: Studio Vista, 1970.)

Incarnadine, Mary Szybist (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2013).

All images, with the exceptions of my own poem and Helen Vendler’s arrangement of George Herbert’s “Prayer,” are taken from Berjouhi Bowler’s book The Word as Image.

—

Mary Szybist's Incarnadine won the 2013 National Book Award for Poetry. Her first collection of poetry, Granted (2003), was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her work has appeared in the Iowa Review and Denver Quarterly and was featured in Best American Poetry (2008). She is an associate professor of English at Lewis & Clark in Portland, Oregon.